Mars Used To Be Wet, With Rain And Snow Falling From The Sky

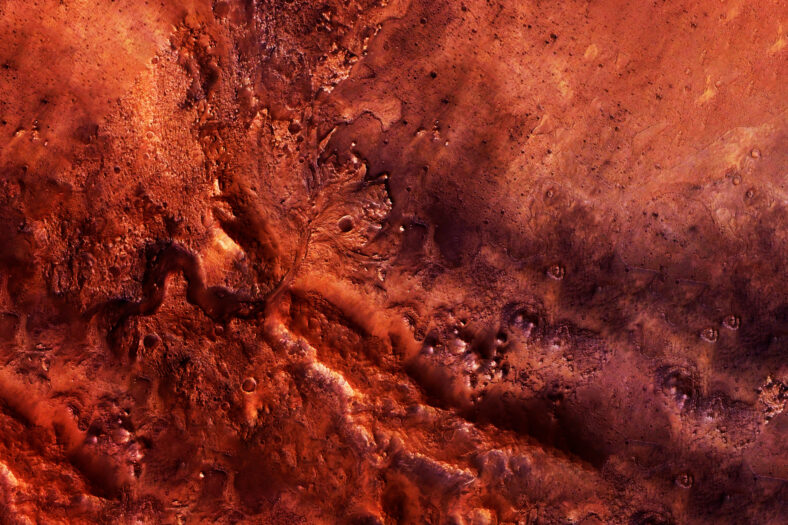

Billions of years ago, Mars was once relatively warm and wet, with rain or snow falling from the sky and rushing rivers that led to hundreds of lakes. This is a much different image from the frigid wasteland we know the Red Planet to be today.

A new study from geologists at the University of Colorado Boulder suggested that ancient Mars likely had heavy precipitation that fed many networks and channels.

In this day and age, most scientists agree that some water existed on the surface of Mars during the Noachian epoch, which was roughly 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago.

But it was always unclear where that water came from. Others believe that ancient Mars was only ever cold and dry, never warm and wet.

At the time, the sun was only about 75 percent as bright as it is today. The highlands around the Martian equator may have contained ice caps that occasionally melted for short periods of time.

In the new study, the research team investigated the warm-and-wet versus cold-and-dry theories. They looked at computer simulations to explore how water may have shaped Mars’ surface. They found that precipitation from rain or snow seemed to have formed the surface features on Mars today.

“It’s very hard to make any kind of conclusive statement,” said Amanda Steckel, the lead author of the study. “But we see these valleys beginning at a large range of elevations. It’s hard to explain that with just ice.”

Around Mars’ equator, there are vast networks of channels that spread from the highlands and branch out into lakes.

Currently, NASA’s Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in 2021, is exploring the Jezero Crater, the site of an ancient lake.

Sign up for Chip Chick’s newsletter and get stories like this delivered to your inbox.

During the Noachian epoch, a river emptied into this region, depositing boulders to create a landform on the floor of the crater.

The team studied the planet’s ancient past by drawing on a model of the landscape’s evolution on synthetic terrain that resembles the area of Mars closest to the equator.

In some cases, the team added water from falling precipitation or included melting ice caps. Then, they let the water in the simulation flow for tens to hundreds of thousands of years.

The researchers analyzed the patterns that formed and found that the scenarios produced very different planets. For the scenario with the melting ice caps, the branching valley heads formed mainly at high elevations.

In the precipitation examples, the valley heads were more widespread formed at elevations from below the average surface of the planet to more than 11,000 feet high.

The predictions were compared to data from Mars taken by NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Odyssey spacecrafts. The precipitation examples aligned more closely with the Red Planet.

Overall, the results have helped scientists learn more about Mars’ ancient climate and even provided insights into the history of our own planet.

The study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

More About:News