Some Cancer Genes Could Play A Role In Protecting You

New research suggests a genetic mutation previously believed to promote esophageal cancer might actually play a protective role during the disease’s early stages, and the unexpected discovery could help doctors identify individuals at higher risk for cancer.

“We often assume that mutations in cancer genes are bad news, but that’s not the whole story. The context is crucial. These results support a paradigm shift in how we think about the effect of mutations in cancer,” explained Francesca Ciccarelli, the study’s senior researcher.

According to the National Cancer Institute, the five-year relative survival rate after being diagnosed with esophageal cancer was 21.6% from 2014 to 2020 in the United States.

However, the UK has one of the highest rates globally of esophageal adenocarcinoma, a subtype of this disease that’s becoming increasingly common.

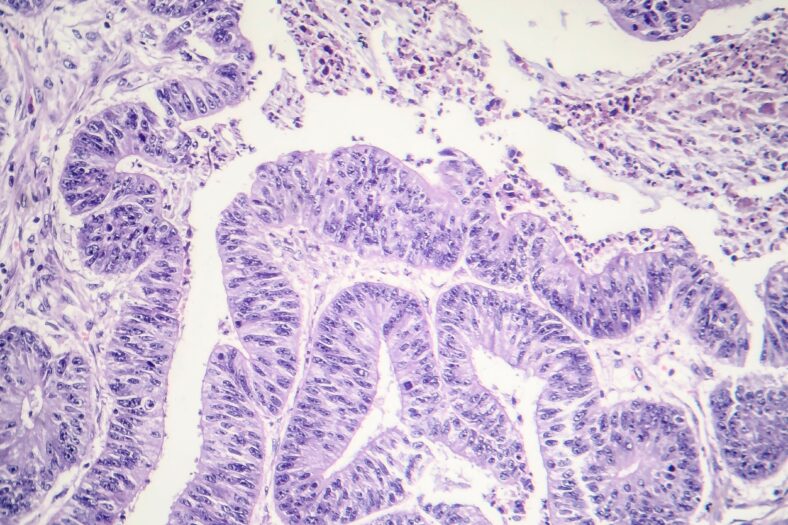

This form of cancer arises from Barrett’s esophagus, “a condition in which the flat pink lining of the swallowing tube that connects the mouth to the stomach (esophagus) becomes damaged by acid reflux, which causes the lining to thicken and become red,” says the Mayo Clinic.

Still, each year, just about 1% of individuals with Barrett’s esophagus go on to develop cancer. In the latest study, the research team set out to explore why some cases advance to esophageal adenocarcinoma as opposed to others, aiming to enhance methods for predicting and treating this cancer form.

They examined an extensive gene sequencing dataset that included samples from over 1,000 individuals with esophageal adenocarcinoma, as well as more than 350 with Barrett’s esophagus.

Surprisingly, they discovered that mutations in a gene known as CDKN2A were more frequent in people with Barrett’s esophagus who didn’t develop cancer.

This result was shocking since CDKN2A, a well-known tumor suppressor gene, typically plays a crucial role in preventing cancer across various types.

Sign up for Chip Chick’s newsletter and get stories like this delivered to your inbox.

The study revealed that when normal esophageal cells lose the CDKN2A gene, it can encourage the formation of Barrett’s esophagus.

At the same time, this loss appears to protect cells from losing another crucial gene, p53, which is a tumor suppressor known as the “guardian of the genome.” The absence of p53 significantly accelerates the progression from Barrett’s esophagus to cancer.

So, the researchers discovered that cells losing both CDKN2A and p53 became weaker and less capable of competing with surrounding cells.

This effectively stopped cancer from developing. Yet, if CDKN2A is lost after cancer has already begun to form, it actually drives the disease to become more aggressive and leads to poorer outcomes for patients.

Ciccarelli compared CDKN2A’s dual role to the Roman god of transitions, Janus, who has two faces: one looking to the past and another to the future. She pointed out how we often think about cancer mutations as either harmful or harmless.

“But like Janus, they can have multiple faces, a dual nature. We’re increasingly learning that we all accumulate mutations as an inevitable part of aging,” Ciccarelli detailed.

“Our findings challenge the simplistic perception that these mutations are ticking time bombs and show that, in some cases, they can even be protective.”

The study’s results could reshape how we evaluate cancer risk. For individuals with Barrett’s esophagus, the presence of an early CDKN2A mutation without accompanying p53 mutations might suggest a lower likelihood of the condition progressing to cancer.

Conversely, if CDKN2A mutations occur later in the disease, they may indicate a worse prognosis. More research is necessary to figure out how these findings can be translated into improved care for patients.

To read the study’s complete findings, which have since been published in Nature Cancer, visit the link here.

More About:News